Responses to a Pandemic: Past and Present

Abigail Agresta / April 9, 2020

“…Some people were of the opinion that a sober and abstemious mode of living considerably reduced the risk of infection. They therefore  formed themselves into groups and lived in isolation from everyone else. Having withdrawn to a comfortable abode where there were no sick persons, they locked themselves in and settled down to a peaceable existence…

formed themselves into groups and lived in isolation from everyone else. Having withdrawn to a comfortable abode where there were no sick persons, they locked themselves in and settled down to a peaceable existence…

Others took the opposite view, and maintained that an infallible way of warding off this appalling evil was to drink heavily, enjoy life to the full, go round singing and merrymaking…and shrug the whole thing off as one enormous joke…for they would visit one tavern after another, drinking all day and night to immoderate excess[.]

…There were many other people who steered a middle course between the two already mentioned…Instead of incarcerating themselves, these people moved about freely, holding in their hands a posy of flowers, or fragrant herbs…which they applied at frequent intervals to their nostrils[.]

…Some people, pursuing what was possibly the safer alternative, callously maintained that there was no better or more efficacious remedy against a plague than to run away from it.” (Giovanni Boccaccio, trans. G. H. McWilliam, Decameron)

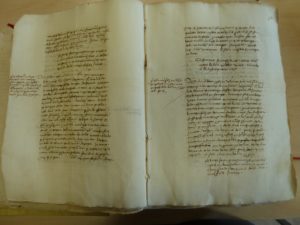

In the prologue to the Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio described how Florentines responded to the Black Death of 1348. As this new disease loomed over Europe, medical recommendations relied on pre-existing knowledge about health maintenance. Just as we are told to wash our hands and stop touching our faces, medieval Florentines were told to eat well, get enough sleep, and avoid activities that opened their pores to outside influences (like hot baths and sex).

As Boccaccio (and now we) know from experience, however, recommendations are one thing, and human choices are another. Some go all in, some resist even the bare minimum, and some try anxiously to strike a balance. And of course, like the Florentines, we are in unknown territory. Who’s to say for certain which approach is right? Do posies of flowers keep you safe? Do cloth masks? Perhaps it’s better to avoid going out at all?

As Boccaccio (and now we) know from experience, however, recommendations are one thing, and human choices are another. Some go all in, some resist even the bare minimum, and some try anxiously to strike a balance. And of course, like the Florentines, we are in unknown territory. Who’s to say for certain which approach is right? Do posies of flowers keep you safe? Do cloth masks? Perhaps it’s better to avoid going out at all?

Boccaccio is of course focusing on those who had choices: those who could, if they chose, shut themselves at home, carouse through the streets or flee the city altogether. Then, as now, only the privileged had such options.

The Black Death of 1348 was only the first of a series of plague outbreaks that passed through Europe in the medieval and early modern  periods (c. 1350-1720). As plague returned again and again, the rich came to focus on a single strategy: flight. Those who could afford it abandoned cities infected with plague. As plague became increasingly a disease of the poor, city governments took stricter measures to keep it that way. The city government of Valencia first allocated funds for the poor during the plague of 1494. The money was to be used for “guards…and nails and iron bars” to lock up the houses where poor people had died.

periods (c. 1350-1720). As plague returned again and again, the rich came to focus on a single strategy: flight. Those who could afford it abandoned cities infected with plague. As plague became increasingly a disease of the poor, city governments took stricter measures to keep it that way. The city government of Valencia first allocated funds for the poor during the plague of 1494. The money was to be used for “guards…and nails and iron bars” to lock up the houses where poor people had died.

We cannot know for certain what strategies will save us from this current plague, but we can recognize, as our medieval counterparts did not, how epidemics exacerbate existing inequalities. And hopefully we can use our funds for more humane purposes.